It’s a fun little debate that pops up every couple of years: do we have a right to choose to die?

It’s a fascinating question that taps into some of the biggest social debates; the sanctity of life, the right of individuals to make their own decisions, and the question of whether the state should protect our lives or our liberty when they come into conflict.

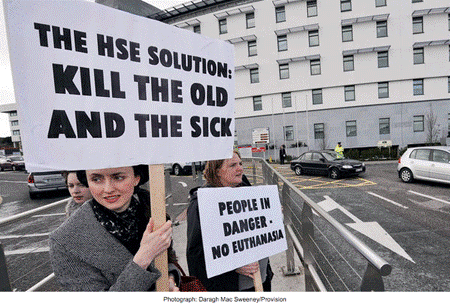

Unfortunately, as with so many interesting debates on the big questions, the nutters from both sides quickly get their hands on it and we end up with newspaper headlines along the lines of “THEY’RE COMING FOR YOUR GRANDMA!”.

Given that a massive portion of human culture revolves around hiding from, preventing, or fearing death, this shouldn’t be too much of a surprise. When everything from cosmetic ads, medical science, government regulation and even the hardcoding of our genes are telling that death must be fought at all costs, the idea that a person might want to die is hard to comprehend.

You only need to look at the vast amounts of money and resources invested into preventing suicide (an act which is technically illegal in many countries) to see how important we think this is. And given the enormous emotional cost suicide can have on families and friends left behind – not to mention the fact that suicidal behaviour is more often a symptom of psychological problems than a genuine wish to die – you’re going to be hard pressed to find anyone who thinks it’s something we should accept or allow.

But euthanasia is distinctly different from this. Whereas suicide largely involves an irrational or emotion-fueled attempt to escape from one’s problems, euthanasia is generally a very deliberate decision made by a person facing the hardest reality of them all; a life that is worse than death.

Terminal diseases, degenerative conditions, life-destroying acquired disabilities or ailments that cause permanent, extreme pain are all pretty standard examples – lives so serious or permanently diminished that continuing to live will lead to little good and plenty of suffering.

But even in the face of these extreme cases, the idea that anyone can rationally decide to end their life is an oxymoron for many people. But is this desire to preserve-life-at-all-costs justified, or is it just an emotional reaction to a situation we’d rather not be facing?

Some lives are more sacred than others?

More often than not when people protest the idea of euthanasia, the ‘sanctity of life’ is the rallying cry. Whether it is based on religious or more philosophical foundations, the argument is essentially the same; life must be preserved because life is everything. Life is our one and (probably) only chance to experience the universe/god(s) creation and death is the ultimate loss of that experience. Death is irrevocable and marks the end of everything about an individual – what experience in this life, even horrible suffering, could be worse than ceasing to exist?

And that’s even before you consider what a god might do with you once he found out you decided to bail before he wanted you to. According to most religions at least, he wouldn’t be terribly pleased.

There’s no denying that these arguments have emotional weight – indeed it is the overwhelming uncertainty that surrounds death that lends it much of its fear. But once you move past the existential dread, arguments about the sanctity of life don’t really add up too well.

First of all, it’s interesting that life only seems to be sacred when it involves humans. Most of us don’t hesitate to eat meat, squash bugs or kill bacteria despite all these creatures being obviously alive (somewhat of a pre-condition for us being able to kill them after all). But whereas most of us would argue that a human life is far more valuable than an animals, this challenges the idea that life is inherently ‘sacred’ by implying that the value of life can be lesser in some circumstances – if it’s ok to kill a bug because it lacks intelligence, then what if a person is similarly unintelligent? And if killing a cow is ok because its entire potential can be summed up as ‘eat, sleep, breed’, then what does this imply for a human who can’t even do those three things for themselves? Or that doesn’t want to do those things anymore?

But even if we choose to ignore this issue and focus on human life exclusively, what about the hundreds of thousands who’s sacred human lives are ended every year through preventable diseases, violence and malnutrition? Compared to the relatively tiny number of people who wish to willingly end their lives, this is a far, far bigger problem – so why aren’t these advocates for life-at-all-costs focusing on poverty instead?

Poke too deep into the ‘sanctity of life’ argument and it tends to fall apart. And as for the fear that god might be angry at those that choose to check out early, I maintain that any being that is both omnipotent AND omnipresent is going to have a slightly more advanced moral approach than ‘Don’t break the rules or you get smacks’.

Euthanasia or Eugenics?

A slightly more nuanced argument that crops up against euthanasia is that it sets a dangerous precedent. As nations around the world continue to abolish the death penalty as a brutal and irrevocable method of punishing convicted criminals, how can we possibly be considering granting the state the right to kill the innocent? Worse, to kill some of the most vulnerable people in our community – the very people left-wingers argue the state should protect the most?

While it definitely looks sound on paper, this argument falls foul of a couple of logical fallacies.

First of all, to compare the death penalty to euthanasia is a ‘false equivalence’ fallacy at its best – the process of ‘executing criminals against their will’ is about as far removed from ‘allowing a person to end their own life if they wish to’, as having your car stolen is from choosing to sell it – one is a choice, the other most definitely is not.

And secondly, to imply that allowing euthanasia in some circumstances will lead to it being allowed or even forced in other circumstances is a clear example of a ‘slippery slope’ fallacy – government legalising one thing does not in any way allow them to open the flood gates and make anything they want legal as well. And since the whole point of the euthanasia movement is decrease the state’s interference in our lives, the fear that it might eventually lead to government ‘mercy killings’ of the sick, poor and old, misses the point entirely.

The benefits of death

These may be good rebuttals of arguments against euthanasia, but can euthanasia itself be justified ethically? It may not be as terrible as we think it is, but there’s no denying that death is very, very final – laws that that make death easier should not be entered into lightly.

Happily the argument for euthanasia is very straight-forward; where the costs of living outweigh the benefits, and the person whose life it is decides they would, on the balance of things, rather not go on living, then they should be allowed to end that life.

While this is very much a utilitarian approach to things (costs versus benefits), it can also be viewed as a matter of property rights; this is my life and any decisions about whether it continues or ends are entirely, indisputably my own. Just as no one has the right to end my life against my will, so too no one should have the power to preserve my life should I wish to end it.

But both of these arguments beg the question of why suicide is different to euthanasia – what does it matter why a person wishes to die? From a ‘property rights’ point of view the decision is theirs and theirs alone to make. And even from the far more complex utilitarian perspective, it is hard to argue that if a person jumps off a bridge, they thought the benefits of continuing living outweighed the costs. Even if the distress they felt was a symptom of some psychological problem, how does this change the fact they found death preferable to the suffering they were experiencing?

Do you deserve to run your life?

To find a distinction here we need to refer to another ethical concept: autonomy, or the degree to which an individual does or should control their own life. While this idea is hotly contested, it is generally agreed that to be worthy of full autonomy, a person must be both completely rational and fully informed about the decision they are making. Since literally all human beings cannot reach these lofty standards, we have institutions such as law, social norms and traditions that aim to guide our behaviours. People who are particularly unworthy of autonomy are usually given into the care of institutions until they improve; schools for the poorly informed and psych wards for the seriously irrational.

Obviously the ‘property rights’ approach mentioned above flies right in the face of this, arguing that control of one’s life must be absolute; whether I am rational or well informed is irrelevant. But there are plenty of situations in life where this sort of unlimited freedom is unacceptable – generally when it starts to hurt others around us. It’s all very well to argue my life is my own business and no one else’s, but if I choose to end that life by throwing myself in front of a bus, I directly damage the lives of the bus driver, the passengers, emergency service workers, everyone caught in the resulting traffic jam, and any friends and family I leave behind.

From a utilitarian perspective, autonomy becomes relevant when judging the costs and benefits of living or dying, because to put it frankly, human are pretty terrible at making these sorts of judgements well.

If you are suffering from depression, a serious psychological condition or intense emotional distress, you are by definition viewing reality from a warped and inaccurate perspective – just because you feel terrible now does not mean things won’t improve in the future. Psychological conditions and depression can be treated, and emotional trauma recovered from in time. But during those dark moments when you go to weigh up the costs and benefits of living, the answer you get is going to be unreliable and tends to be inaccurately biased towards the negative. As such your autonomy comes into question: you are not rational and thus your understanding of your situation is confused and inaccurate. Allowing you to control whether you live or die at this point would be a mistake to say the least.

On the other hand, people considering euthanasia tend to be paragons of autonomy; both extremely well informed about their current situation and future prognosis (usually thanks to the medical system), and having spent enough time sorting through their situation in order to be quite rational when considering these facts. There are definite exception to this, but broadly speaking it is fair to say that terminal patients do not want to die – were the option to recover and live a healthy life available, they would most definitely take it.

But for them that future is not possible, and rather than deny or fight this reality (which would be the irrational/delusional approach here), they choose instead to embrace it and end their lives on their own terms. Faced with the harsh reality of the suffering that they knows awaits them and their loved ones as their condition gradually degrades their quality of life and eventually kills them, they have made the the cold, hard, logical decision that they would prefer to die now and avoid this frankly pointless suffering.

In such a situation, where a person is well informed about their situation, diagnosed to be of a rational state of mind by authorities, and having considered the costs and benefits of continuing to live, decided that they would prefer to die, on what basis can we deny them this?

How can we tell a person who has accepted his mortality and seeks only to leave life with dignity and free from pain, that he must suffer until the bitter end because euthanasia makes us uncomfortable?

Death is the only true certainty of life. And while it may indeed terrify us that anyone would seek oblivion willingly, to let our fears cloud the stark reality that people such as Peter have faced and come to terms with will lead only to injustice.

My step-mother and 2 uncles spent the last weeks of their life experiencing horrific suffering. To deny someone death with dignity is, IMO, inhumane, to say the least. You have made many excellent points in this superb post, such as this:

“Poke too deep into the ‘sanctity of life’ argument and it tends to fall apart.”

Indeed it does.