Ok I’m back and pleased (though also vaguely disappointed) to report that I was not abducted by The Man for my subversive activities.

https://giphy.com/embed/hICLOdBZxwoLe

What’s the point in raging against the machine if the machine doesn’t notice, dammit.

Three weeks ago I started this two-parter off by detailing a rather cruel, but pretty compelling experiment I ran with my uni class, where they elected representatives do divide up a block of chocolate between the class. Through equal parts intentional bad system design and simple human nature, those representatives screwed the rest of the class over and took all the chocolate for themselves. Apart from creating some quality student drama, and giving me a pseudo-legitimate excuse to mess with my students, this experiment demonstrated one very subtle point – the point where the students were screwed over came a long, long way before the point where they realised it.

The context for all of this was the Social Credit System currently being developed and implemented in the Republic of China. For those who prefer the article to provide an overview rather than having to actually read up on it yourself (gotta admit, I kinda fall into that category), the gist is simple: this is a system the Chinese government has set up to reward positive, and penalise negative social behaviour. ‘Good’ behaviour such as donating blood, increases your score, and ‘bad’ behaviour like smoking against the rules, decreases your score. Your social credit has nothing to do with the law – you won’t be jailed for a bad score – but you can still be punished in a number of ways, including better or worse flight options, priority in use of public facilities, subsidies with private companies, and even the length of your wait in a hospital.

This is one of those systems that makes a lot of sense on paper – after all the government already dictates some of our behaviour through laws, and encourages certain non-legal behaviours (such as healthy eating) through education and economic incentives, right? So surely this is just an extension of that?

Not that they’re necessarily any good at it, but hey.

But this Social Credit System differs in two major ways;

- Consequences – As mentioned before, the idea of governments going beyond mere legal regulation and trying to encourage us to behave well is hardly unprecedented. But whereas these programs might try to educate citizens or incentivise good behaviour, the Chinese Social Credit Scheme takes it to a whole new level by attaching your behaviour to an over-all score. So while many governments might get stroppy with you for eating badly, refusing to vote, or being an arsehole to your waiter, the consequences for doing so are usually very limited, and more importantly, confined to that specific act. This Social Credit System ensures that each and every ‘bad’ behaviour you ever commit will follow you around permanently, until you can off-set it with a ‘good’ action.

- Invasiveness – Of course the idea of your behaviour being reflected in a score raises the question of how that behaviour gets detected. Spitting on the footpath might indeed get you a negative score, but that doesn’t mean a whole lot if no one sees you do it, right? And even if they do, who’s going to take the time to bother reporting such a minor, totally legal act? Well fear not citizen, because the Chinese Government also happens to run the most extensive public and private surveillance network the world has ever known, and has recently made massive strides in employing facial recognition technology to identify and detail wanted criminals. The idea of government surveilling innocent citizens is already worrying enough, but combined with a system that give them an excuse to proactively monitor and catalogue even social behaviour, and you have a situation where the government can effect control over every part of a person’s life.

That said it could be argued that both these extraordinary qualities could actually be beneficial – I’ve stated myself on this blog before that ethics which lack consequence are just empty words. And it is true that one of the only two ways in which a society could realistically reach a utopian state is through total control over behaviour to ensure perfect conduct (the alternative being total freedom for a totally reliable populace – different methods, same result).

Either way you cut it, both these societies involve a lot of people behaving themselves.

But this in turn assumes that the ethical system we are all held to is, y’know, good.

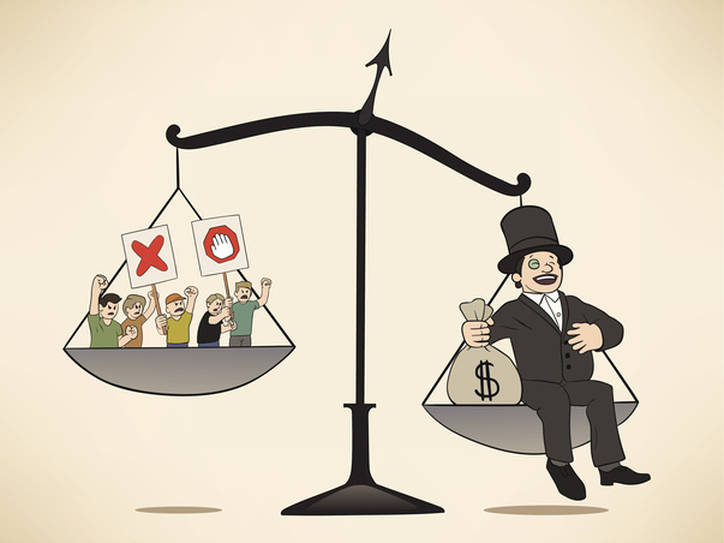

And right there is the problem with this Social Credit dealie – by granting the government (and their corporate mates) such total control over our behaviour, both legal and social, we also hand them total control over what ethical standard we will be held to. And once they have this control, these standards can be changed. And there will be sweet bugger all anyone other than those in charge will be able to do about it.

Because we already handed over our power.

As with the experiment with my students, the point where society realises that it’s in the hands over a despotic government will come significantly later than the point where we enabled, and thereby endorsed, such a system.

And in case you’re tempted to take refuge in the idea that this is all just a Chinese problem – where admittedly the government has a pretty well-documented history of squashing human rights and suppressing its citizens for its own ends – then I strongly suggest you think again. Of course most western/developed nations are a long way away from the Chinese government’s degree of control, but that’s not the point – the point is whether we can get there, and whether there are any signs that we might be headed in that direction.

And if that’s the question, then I have some very bad news for you: between the Patriot Act, the horrible but completely legal and likely still ongoing NSA spying operations, efforts by the Australian Government to consolidate citizen biometric data, and the near universal efforts by governments world-wide to exert control over the internet (net neutrality, SOPA, data retention, etc), it’s pretty clear that there are plenty of governments who can see the appeal of the new Chinese system. All of which is hardly surprising, since it would by its very nature, greatly increase the power of those in government – something which is always in a person’s interests.

They’re always the villain, until YOU’RE that guy.

All of this comes back to the second question I ended on last time: At what point must a citizen stop operating within a system, and choose to break it instead?

Do not for a second think that I write that sentence without fully understanding what that might mean. Choosing to break a system we all live and operate within means doesn’t just mean disrupting it or advocating for change – it means seeking to overthrow entire structures, by whatever means are necessary to do so.

You probably think I’m talking about riots. In reality we’re probably talking about terrorism. Maybe a civil war if you can wrangle it.

That doubtless sounds extreme, but consider the task in front of you: a government with not only control over the laws we operate within and the legal right to enforce those with violence, but a government with proactive influence over near every aspect of how citizens conduct themselves. How is peaceful protest possible within such a system, when virtually any form of dissent can be detected and punished almost immediately? How can opposition be mobilised when you each carry a visible score that shows your conformance to the party’s morality? Two low-scorers talking to each other is a dead give-away for security forces that dissent is likely brewing.

Undermining such a massive concentration of power through mobilisation and education is virtually impossible, because the government already controls both those options and worse, your ability to gain more control of them. Power facilitates the accumulation of more power, and the powerless slide further and further into weakness. Fighting back from such a disadvantage requires not merely challenging the powers that be, but overthrowing them completely, decisively and without mercy. And since the state has the legal right to use force against such threats, you too will have no choice but to resort to force in turn. And thus you’ve become a terrorist – or freedom fighter if you prefer. Either/or.

Pot-a-to, po-ta-to.

Of course, the problem with such an approach is that, despite being both highly pragmatic and having justice on your side, you have absolutely no guarantee of success – in fact, lacking intervention by powerful external allies, the same power differential that forced you to rebellion in the first place, is likely to get your arse kicked in armed conflict as well. But faced with such totalitarian power, what other options do you have?

And this is where we come back to the lesson from the chocolate experiment: the point where people get screwed over comes well before the point where the negative effects are experienced. By the time you’re considering armed rebellion as an option, you’ve already been quite thoroughly screwed over, and all your options are bad ones.

Therefor the best option is to avoid getting screwed over in the first place. And that requires paying attention to threats to our freedom long before we start seeing our rights disappear.

And when it comes to the threat posed by Social Credit Systems in our own nations, the point where we are getting screwed is right now. If you want to avoid a future where you a faced with the grim choice between bowing to the social order or putting your life on the line to fight it, then this is the moment for you to take action.

Incidentally, I realise this is all sounding very Libertarian of me. But what the Libertarians haven’t seemed to work out yet is that it doesn’t matter who is in charge – the government, corporations, religious groups, a random PTA – if you concentrate this level of power into ANYONE’S hands, the threat is the same. Totalitarian governments are dangerous, but so is their precious ‘free market’.

So how do we fight back? Well the good news is that, right now, your options are plentiful:

- Give zero tolerance for power grabs by powerful groups. Don’t accept the argument that more authority is needed ‘for national safety’ without solid proof that such a threat exists, AND that the extra authority is necessary to deal with it.

- Reject fear as a foundation for decision-making, and appeals to fear in persuading you about anything. If danger exists, so should objective evidence of that threat.

- Demand transparency and accountability for how your data is used by anyone you give it to. Ask yourself the question; if Google started seriously threatening your privacy tomorrow, what would you do about it? What could you do about it? Until this question can be answered with certainty, we must not accept the status quo.

- Reject the ’if you’ve got nothing to hide, you’ve got nothing to fear’ fallacy and refuse to tolerate it from others.

And above all else, if there is one thing we badly need to start doing, it is to stop giving automatic respect to authority and those who wield it. Far, far too many times since Trump was elected I have heard the phrase “I may not like him, but he is the President, and we should respect the office”.

Why?

No, seriously, why? The office of the President of the United States of America is possible the most powerful in the entire world. It commands massive economic, social and military power – why the hell does it also deserve your automatic respect, when everything we’ve ever learned about such concentrations of power tells us that whoever holds such an office will almost, without exception, fall to corruption to some degree or another?

We’re not exactly lacking for examples of abuse of power here, are we?

Power is its own reward, it does not deserve bonus respect – if anything it should automatically bring suspicion and disrespect by default, because power both allows and encourages its own abuse.

- Stop thanking soldiers for their service and start asking them whether the wars they fought for were justified, and whether their commanders spent their lives for worthy goals.

- Stop giving police officers the benefit of the doubt, and start holding them to the higher standards that anyone with a legal mandate to deliver force should suffer.

- Stop gushing over CEOs and captains of industry, and start asking whether the private rewards they reap justify the public harms they may inflict.

- And above all else, turn a hard, merciless eye on anyone who would dare suggest that they are worthy of representing you in public office. For these people ask to be placed in power over you and yours, and not answer for their conduct in any real way until the next election, and possibly not even then. These are the ultimate threats, the most dangerous of individuals, capable of vastly more harm than any criminal, and all the more dangerous if they believe they are acting in the public good.

So how to answer out question: At what point must a citizen stop operating within a system, and choose to break it instead?

Simple. A citizen must break any system that gives power out without accountability for its use.

For wherever power concentrates, trust must die.

Pingback: The Ethics Of… The Pure Idiocy of Coles’ Little Shop | The Ethics Of